The History of Jamaican Music 1959-1973

Archived with permission from The GlobalVillageIdiot.net 10/31/00

It was Bob Marley who made reggae into an international phenomenon. In

the wake of his success in the 1970s came a host of other names, and it wasn't

long before reggae became an established genre of music. But reggae was simply

the growth, the development, of what had been happening in Jamaican

music.Beginning with ska, and then rock steady, the loudest island in the world

had declared its real musical independence, and had already made an imprint on

the world, albeit a small one.

If you want to take it back to the beginning, you have to blame it on jazz.

One of America's great contributions to musical culture, it swept around the

world. Through radio broadcasts and records, Jamaica, then still and British

colony, got the fever in the 1940s. Bands sprang up to entertain tourists, like

Eric Dean's Orchestra and future giants like trombonist Don

Drummond and sax man Tommy McCook learned the licks and honed their

chops on the music.

With the advent of the 1950s, American popular music began to fragment. In

jazz, be-bop became the new movement. Rhythm and blues, the black style formerly

called race music, started coming on strong. The era of the jazz orchestra was

slowly fading as music grew harder, stronger, more youthful. That spread to

Jamaica, just as it did to other parts of the globe.

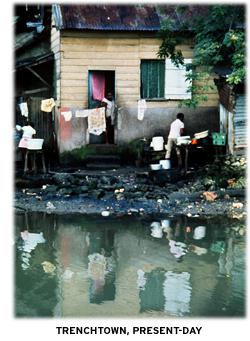

And Jamaica itself was beginning to change. It had been a mostly rural

economy, but now people were flooding into the capital, Kingston, in search of

their own piece of postwar prosperity. On the weekends Kingstonians old and new

would gather for dances in the open spaces called ‘lawns' all over the city,

where sound systems (essentially loud, primitive mobile discos) would throb with

the latest sounds from the States. If you didn't have a radio - and in the poor

economy, many didn't - this was how you heard the new records.

R&B was the diet of the sound systems. Fast, raw, and with a thick beat,

it played well to both young and old. Sound system owners would travel to the

U.S. to buy new records, or have agents ship them over. It was a constant war to

have the newest, freshest sounds. A popular disc might be played 15 or 20 times

during the course of a dance.

By the mid-50s two sound systems stood head and shoulders above the crowd in

Kingston - Duke Reid with the Trojan, and Clement Dodd with Sir

Coxsone Downbeat. Competition between them was fierce, and would last well into

the next decade, one of the major catalysts for the growth of the Jamaican music

industry. The sound systems had no choice but to play American records, because

the island simply had no recording facilities. Stanley Motta had made

some tapes of the native mento folkloric music, but it wasn't until 1954 that

the first label, Federal, opened for business, and even then its emphasis was

purely on licensed U.S. material.

The kick start to homegrown Jamaican music came with rock'n'roll. As it

became the dominant form in America during the latter half of the ‘50s, the

number of R&B releases dwindled to a trickle - not enough to satisfy the

insatiable appetites of the sound systems. Something had to be done.

The first person to act was Edward Seaga, who would go on to become

Prime Minister of Jamaica. In 1958 he found WIRL - West Indian Records Limited -

and began releasing records by local artists. They were blatant copies of

American music, but that barely mattered; they were new and playable on the

sound systems. The same year, Chris Blackwell (a well-to-do white

Jamaican, related to the Blackwells of Cross & Blackwell fame) got his own

start as a record magnate, putting out a disc by the then-unknown singer

Laurel Aitken, and within twelve months both Reid and Dodd, seeing the

possibility of having records available exclusively on their systems, had jumped

on the bandwagon with the Treasure Isle and Studio One labels, respectively. And

once a pressing plant, Caribbean Records, had been established on the island

(meaning the masters no longer had to be shipped to America for pressing), the

Jamaican recording industry was well and truly born.

From that beginning, it was inevitable that Jamaican music would find

its own identity sooner or later. The biggest surprise is that it happened

so quickly.

The sound called ska came into being in 1960. At least, that's one of

the stories. Other sources claim 1959. Or ‘56. Or ‘61. In other words,

almost as many people claim to have invented it as there were producers on

the scene. There's no doubt, however, that Jamaicans were ready for

something new. The homegrown copies of R&B just didn't have the punch

of the originals.

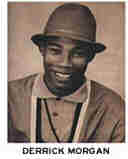

"We were trying to imitate," noted singer Derrick Morgan, "but

when we did it, it wasn't real." While so many grab the credit for ska,

critics generally agree its father is Prince Buster. Cecil Campbell

(his real name) had been an employee of clement Dodd, leaving in 1960 to

set up his own Supertown sound system. Like others before, he turned to

record production, beginning with a mammoth session of 13 songs for his

new label, Wild Bells.

"On the way home from a session with Duke Reid I met Prince Buster,"

recalled Morgan. "He asked me to come and sing - he was just starting out.

I told him yes. We did 13 songs, and they were all hits. He was supposed

to give Duke Reid half the money, but in the end he just have him one

song, the one he thought was the weakest, by [trombonist] Rico

Rodriguez."

It was one of those events that changed history. Over the course of the

session, something new came into being, which melded the rhythm of

traditional mento music, mixing it with R&B.

" With those tines - "They Got To Go" and "Shake A Leg - they're coming

more into ska," explained reggae historian Steve Barrow, "with the

emphasis on the afterbeat carried by the guitar, because that's what

[guitarist] Jah Jerry did for Buster. Buster said, ‘I told him,

change gear, man, change gear,' and Jerry would give it that afterbeat

syncopation on the guitar."

Now they had something new; all it needed was a name, and that came

from bassist Cluett Johnson, Barrow noted, "because he used to go

around calling everyone skavoovie, and that was a made-up word, but it was

a precedent for a name."

Buster couldn't have guessed he'd be charting the entire future course

of Jamaican music. All he cared about was that the crowds at his sound

system loved his new beat.

But the homegrown music, now readily identifiable, fitted in perfectly

with the mood of the time. With Jamaica receiving its independence,

national pride was running high, and anything uniquely Jamaican was

embraced. Also, the new ska, made by the working classes, was definitely

music of the people, really music of the Kingston ghettoes. The other

sound system operators needed to make their own ska records to compete

with Buster, which they very quickly did.

Discs were made primarily for sound systems, rather than for sale. So

the product was on acetate (also known as pre-releases) which would

quickly deteriorate - by which time they'dalready been replaced with

something new. Still, those with money could buy the records.

"Prince Buster used to sell copies of "Humpty Dumpty" for 50 pounds!"

said Morgan. "You could buy a house for that in those days. And if they

did ever release the songs, they'd put them on white labels, with no

artist credit. But the sound systems did motivate us to record. People

used to come looking for the best, the most excitement, and they wanted

the newest sounds."

Both Reid and Dodd began having their own ska hits, and soon there was

another face on the scene, Leslie Kong, a Chinese-Jamaican who

owned a restaurant called Beverley's, which proved inspirational to young

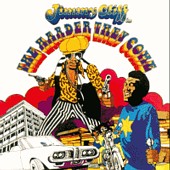

singer Jimmy Cliff.

"Jimmy wrote a song called "Dearest Beverley," remembered Morgan, "and

he went to see Kong to get it recorded. They told him to look for me and

said that if he found me, he could record his song. So he came to my

house. His song was a slow ballad, and I told him no-one would like it,

because we were all doing ska music. So we wrote "Hurricane Hattie" and

"King Of Kings" and we went to meet Leslie Kong."

Although inexperienced, Kong was eager to enter the record business,

and asked if Morgan, by then already well-known, would record a side for

him, "so I recorded "Be Still." And he took on Jimmy Cliff, who was still

Jimmy Chambers then - Beverley's changed his name. And I started recording

for Beverley's."

For Morgan, it was a matter of economic reality. Most producers were

offering musicians $10 a song, Beverley's upped the stakes to $20. And

since no-one was paying royalties, people went where the money was and

laid down tunes as fast as they could. Morgan's defection started a

rivalry between him and Prince Buster.

"In 1962, after I'd left Buster, I made "Forward March!" which was the start

of it. Buster said there was an instrumental break on the record that had been

stolen from him." His response was to release "Black Head Chinaman," aimed

directly at Morgan and Kong. The problem lasted for two years until "the

government finally asked us to stop, because it was causing too much trouble."

While the feud continued, it fueled record sales for both artists. Not that

Morgan needed the boost. Even as new acts like the Wailers and the

Maytals, or solo artists such as Alton Ellis and Eric

Morris came along, he remained the king.

"There were a lot of hits," he said. "There was a time when I had seven of

the top 10, number one to number seven. They used to call me ‘The Hitmaker and

the Hitbreaker.' Every producer used to come looking for me. And every Saturday

whoever had hits in the charts used to go to a club called the Silver Slipper

and sing. They'd pay two pounds a song. I ended up getting 14 pounds one week,

and the other artists didn't like that. But it was me. I'd sing, and people

loved it, and my records sold."

According to Barrow, Morgan was so successful "because he sang soulfully, he

had that sound, but he sang Jamaican songs, things that could only have been

written in Jamaica."

The ska sound swept through Jamaica the way beat music would take over

England a few years later, and the number of recording acts proliferated to meet

the demand. It offered a start to a numbers of artists whose careers still

continue. The Maytals, led by Toots Hibbert, scored a string of hit

singles. Ken Boothe.

It was also the beginning for a young Robert Nesta Marley who was part

of a vocal trio called the Wailers. Marley had received his first push from

Kong, but once he began working with Neville ‘Bunny' Livingstone and

Peter Tosh as the Wailers, recording for Clement Dodd at Studio One, the

magic began. "Simmer Down" was one of the major hits of 1973; rumor has it that

the record sold 70,000 copies in just a few weeks.

By now, sound systems had become big business (Dodd alone owned four), and

that meant more and more records were needed. In turn, that required musicians.

The main studios had their own bands to back singers and also release

instrumental tracks - another of ska's backbones.

In 1962, tenor sax player Tommy McCook was asked to join the Studio One band,

but "back then I was a John Coltrane disciple, I was into the jazz scene.

I wasn't familiar with ska. I didn't start recording it until a year later,

after listening to the music with Don Drummond. Then I thought I had the feel of

it, so I decided to start recording. My jazz group had broken up and I'd joined

Aubrey Adams's band, playing at the Courtleigh Manor hotel. We all played

in big bands, we all came from a jazz influence. The ska that was being played

changed when I joined the Studio One group. Before that it was a boogie kind of

ska. After I joined it was a jazz-ska thing. I think "Exodus" was my first

instrumental there, and then I started writing for Coxsone. People kept asking

me who were the people on the records - they recognized my sound from the discs.

So I'd tell them who was in the Studio One group, and when I went to the next

session I told [the musicians] to form a group, because people were asking about

them, and people would pay to say them. Jah Jerry said they'd form a group if

I'd lead it. I said I couldn't, because I was still under contract to Adams. And

they still said they'd only form it if I'd lead it. Eventually my contract with

Aubrey was up, and I didn't sign back with him."

And so the most influential instrumental ska band, and certainly the most

famous, began - the Skatalites.

"I formed the group in June of ‘64, and we did pretty good," McCook

continued. "We were going all over Jamaica. We did 14 months on the road before

we disband in ‘65."

Apart from live shows, they recorded a number of hits, like "Guns of

Navarone." With reputations as skilled soloists, the Skatalites were the main

‘band' in a young industry. Most were graduates of the famous Alpha Boys'

School, a Catholic institution which seemed to churn out musical talent -

Roland Alphonso, Jackie Mittoo, and Lester Sterling, any

number of instrumentalists who'd become famous in Jamaican music. And there was

also Don Drummond, perhaps the most gifted of them all, who'd meet a tragic end

in an insane asylum after murdering his common-law wife.

By 1964, ska had become the pre-eminent music in Jamaica, its identity

closely entwined with the country. So closely tied, in fact, that for the

World's Fair that year in New York, the Jamaican government sent over Jimmy

Cliff (as well as bandleader Byron Lee, Prince buster, and Carole

Crawford, the reigning Miss World) in an attempt to export ska to the U.S..

There were performances, and classes were offered in dancing ‘the ska' and ‘the

shuffle.' As history shows, it didn't work.

Ska might not have caught on in America, but in England it was a different

story. But Britain, particularly England, had a growing Jamaican population.

World War II had left the country decimated, both physically and

psychologically. The servicemen who returned came back to a place that needed

rebuilding, both in physical plant and infrastructure, to really make it a land

fit for heroes. The only way was to import labor, so in 1948 the doors were

opened to citizens of the Empire. The money promised was far more than they

could have earned in the colonies (although no mention was made of the higher

cost of living, or the lack of availability of so many things in a country still

living in austerity), that people arrived from all over.

Unsurprisingly, each nationality gravitated to its own, both socially and in

living areas. They needed each other in this foreign place, especially when the

immigrants discovered the promise of riches was no more than words and they

found themselves doing jobs the natives didn't want.

Around people from home, though, things were easier. For the Jamaicans, that

meant importing ideas from the island, one of which was the sound system. By

1956, the first one was operating in England, and soon ‘blues dances,' as they

were known, were a weekend feature of Jamaican communities through out the

country. Once ska hit at home, it made its way across the Atlantic, where it

proved popular with the expatriates. In 1962, three labels were releasing

Jamaican music in the U.K. - Melodisc, which created the Blue Beat label for

ska, with Prince Buster and Laurel Aitken as their main artists; Island, Chris

Blackwell's creation; and R&B. As more and more Jamaicans moved to Britain,

it became a more lucrative market for artists than Jamaica itself.

"You might sell five thousand records in Jamaica, but you'd sell a lot more

over there," Morgan observed.

Aitken, a Panamanian, was one of the first ska musicians to make his home in

England, where his records always sold well, sometimes staggeringly so - "Mary

Lee," an early single, shipped 80,000 copies in England alone. He also made

frequent live appearances in the country.

It took a couple of years, but ska, or blue beat as it was also known, did

manage to break though briefly into the British pop mainstream.

"My Boy Lollipop," by Millie Small was a cover of an old Barbie Gaye

R&B tune. The record became a true international sensation, climbing to #2

in both the U.K. and U.S., which was enough to make part of a generation of

Britons aware of the underground movement happening around them. The Mods

listened hard. For them the music of choice was soul, but there was also a

definite attraction to ska, with its irresistible beat, and also to the sharp

looks of the rude boys, the most fashionable Jamaican youth. Shaved heads, good

clothes, pork pie hats - the rude boys had style, and the mods - some of whom

became skinheads a few years later - copied much of it. There was an affinity of

sorts between the two groups that transcended race. Both were working class, and

had a taste for the good life and strong dancing music. The rude boy phenomenon

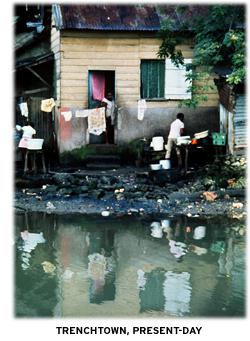

had begun in Jamaica and was soon exported to Jamaicans overseas. At home they

were youth who'd flocked to Kingston after independence, only to find no

opportunity in the city. With no work, and no money, they found themselves

existing in the ghettoes of Trenchtown and riverton City, making money any way

they could, often turning to crime (as in the film The Harder They Come),

forming gangs, making their way in the underworld and even into some of the

armed political groups which were gaining in influence. They were cool, and

‘bad,' as they said. Rude boys lived on society's fringes, outsiders, and

expressed themselves through their dress and their dance. Ska, with its quick

beat, demanded a lot of energy from its dancers. But rude boys didn't like to

move that fast. "They used to dance half-speed to certain ska records,"

explained Barrow, "and the music changed to accommodate that."

Which was the birth of rocksteady.

Ska desperately needed to move on. By the summer of 1966 it had been

around for more than half a decade, and while the songs had grown in

sophistication, the basic rhythm and arrangements hadn't. There was still

the defining off-beat emphasis over a walking bass pattern. The rock

steady concept brought the new idea ska sought.

"The rhythm was experimented with," noted Barrow, "and it was slowed

down because of what was happening with the rude boys in the dancehalls.

Roy Shirley says he made "Hold Them" in 1965. He could have done it

as a slow rhythm, but I don't think it was rock steady. Hopeton

Lewis went in to do a ska tune, "Take It Easy," and he couldn't manage

it on the rhythm, so he said to play it slow. They played it half-speed,

and when it was done, someone said to him, ‘That rock steady, man, that's

rockin' steady.' And that's how the name came about. He claims he was

before Studio One, Beverley's, everyone with rock steady (the record was

released on Federal)."

Roy Shirley says he made "Hold Them" in 1965. He could have done it

as a slow rhythm, but I don't think it was rock steady. Hopeton

Lewis went in to do a ska tune, "Take It Easy," and he couldn't manage

it on the rhythm, so he said to play it slow. They played it half-speed,

and when it was done, someone said to him, ‘That rock steady, man, that's

rockin' steady.' And that's how the name came about. He claims he was

before Studio One, Beverley's, everyone with rock steady (the record was

released on Federal)."

That's one version of the history, and perhaps more likely than some

others. The advent of rock steady has also been attributed to an extremely

hot summer, which forced all the dancers to move more slowly - to rock,

instead of move wildly - and that was reflected in the new sides

appearing. It's also been said the sound came from musicians'

dissatisfaction with the ska beat, and the search for something new.

Whatever the true reason, it was decidedly different from ska.

"It broke up the rhythm," explained Barrow. "It had the effect of

making the bass play in clusters, a pattern, rather than a continuous

line. The drums and everything fell in with that. [Guitarist] Lynn

Taitt was the guy who orchestrated that. Not enough people mention

him. He was one of the great unsung heroes of Jamaican music, and he was a

Trinidadian."

Inevitably, the new rhythm proved very popular ("Take It Easy" sold

10,000 copies in a single weekend) party because it was new, and also

because dancers didn't have to expend so much energy and could stay on the

floor longer.

Whereas Coxsone Dodd and his Studio One label had dominated ska, it now

became Duke Reid's turn in the pole position, as Treasure Isle quickly

established itself as the home of the new sound. He took Alton Ellis from

Dodd, to add to his stable, which included the Paragons and

Dobby Dobson, all backed by a new studio band, the

Supersonics, led by Tommy McCook. After the 1964 breakup of the

Skatalites, McCook recalled, "Coxsone formed the Soul Vendors, and

I was asked to lead it. I said I didn't want to right then, I needed some

rest after being under pressure. About a couple of weeks later I did say

okay, and renamed the band the supersonics. All I had to do was play music

and rehearse the band, unlike the Skatalites, where I'd had to do

everything. We had a steady weekly gig, they were playing salaries, and

that made it easier. Then we became a Treasure Isle recording group. A lot

of the pressure was off me, and we were doing pretty good."

Among the vocal groups they backed for Reid were the Techniques,

one of the best of the era. With hits like "Queen Majesty" and "Love Is

Not A Gamble" they were a major force, and a training ground for a number

of singers who'd progress to solo careers, like Slim Smith and

Lloyd Parks, who worked with the core of Winston Riley and

Frederick Waite.

But the change hadn't edged Prince Buster out of the picture. Having

scored hits himselfduring the time of ska, as well as being one of its

leading producers, he continued to release material, with "Judge Dread" in

particular becoming huge, its castigation of the Rude boy style triggering

a number of like-minded songs from other artists.

Although ska had flared briefly in England, the flame didn't take full

hold until rock steady hit. After that the music's profile rose sharply,

thanks to two factors - the Trojan record label, which licensed a great

deal of Jamaican product, and an artist who enjoyed a string of hits. The

budget-priced Trojan Tighten Up compilations gave listeners volumes

of Jamaican music, and were vital listening to anyone with any degree of

interest. Their sheer cheapness brought a lot of the curious on board,

many of whom proceeded to catch the bug, and explore the music more

deeply. But the person who became the face of rock steady in the U.K. was

Desmond Dekker (born Desmond Dacres).

He'd been a part of Leslie Kong's Beverley stable since 1962, but it

wasn't until 1967 that he scored his first real hit with "007 (Shanty

Town)," one of the many responses to "Judge Dread." In the U.K. the single

(issued by Trojan) went to #12, and began a string of hits for Dekker

which would extend into 1969, by which time Jamaica was already in thrall

to reggae. His biggest song, "Israelites," reached #1 in Britain, Canada,

Sweden, West Germany, Holland, and South Africa, and gave Dekker his only

U.S. chart exposure, climbing to #9.

The nascent skinhead movement, an outgrowth of the Mods, lapped up rock

steady, as well as a singles from the cusp as the genre grew into reggae,

like The Pioneers' "Long Shot Kick The Bucket" and the

Upsetter' "Return of Django," to the extent that in England the

music became known as skinhead reggae.

The prime time of the style was brief, at least in Jamaica, however. It

ran from mid-1966 to the close of 1967 when, according to singer Morgan,

"we didn't like the name rock steady, so I tried a different version of

"Fat Man" (one of his early hits). It changed the beat again, it used the

organ to creep. Bunny Lee, the producer, liked that. He created the

sound with the organ and the rhythm guitar. It sounded like ‘reggae,

reggae' and that name just took off. Bunny Lee started using the world and

soon all the musicians were saying ‘reggae, reggae, reggae.'"

Again, it's up in the air as to who really invented reggae, although

the first record to bear the name was "Do The Reggae" (or "Reggay") by the

Maytals in 1968. According to historian Barrow, it was producer Clancy

Eccles who coined the term, taking street slang for a loose woman -

streggae - and changing it slightly. The music itself was faster than rock

steady, but tighter and more complex than ska, with obvious debts to both

styles, while going beyond them both.

And like any new music, it had its young guns, in this case producers

Lee ‘Scratch' Perry, and Bunny Lee, and engineer Osborne ‘King

Tubby' Ruddock. Perry had worked for Coxsone Dodd, often surpervising

the production work, without receiving the glory and money which went

along with that. Ruddock had worked for Duke Reid, and also ran his own

sound system, Home Town Hi-Fi. His background as an electrical engineer

meant that his system sported some unique, home made gadgets, echo in

particular, that helped set it apart from others.

As well as the upcoming talent behind the board, plenty of new artists

were eager to shine in the studio. Since the established labels already

had their house bands, the new boys had to find their own talent,

musicians with something to prove - and they proved it playing reggae.

Perry was the first of the new crop to hit big, in his case as a

recording artist. "People Funny Boy," an obvious dig at Dodd, sold well,

and gave Perry the impetus to start his own label, Upsetter Records, in

1969. In short order he made it a viable entity with two more hits -

"Tighten Up," by the Untouchables and "Return of Django" from the

upsetters, his house band, which included two brothers Carlton and

Aston Barrett as the rhythm section.

The success helped Perry woo a group he'd worked with at Studio One -

the Wailers. After some initial success, the Wailers had found life under

Dodd difficult. Dodd had befirend Bob Marley, even putting him in charge

of pairing singers and songs for the label, but he'd kept his distance

from the more volatile Peter Tosh and the Rastaman Bunny Wailer. In 1966,

Marley moved to America, where he worked at the line in a Chrysler plant

in Wilmington, Delaware. It was his chance to earn good, steady money,

which he did until he lost his job. After discovering he wasn't eligibile

for welfare, then receiving a draft notice, he returned to Jamaica and

music, writing new material, some of which would appear on Wailers' albums

in the ‘70s.

By late 1967 the Wailers had left Dodd, and the following year formed

their own label, Wailin' Soul, which proved a failure, in part because all

three members spent time in jail - Tosh for obstruction during a

demonstration against the regime in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and Wailer

and Marley for possession of marijuana. Even though the label collapsed,

the Wailers weren't discouraged.

They began again with the Tuff Gong label. While it didn't make them

rich, they made enbough to survive, and they also signed with Jad, the

company run by singer Johnny Nash as songwriters, earning $50 JA

each per week. That the band had ability was beyond doubt; the problem was

that they were unable to put together the lucrative overseas deals which

would catapult them to the next level. Their rebellious attitude scared

off potential partners. So when Perry came along, they leaped at his

chance. The Wailers and the Barrett brothers became friendly, and Aston

Barrett became the Wailers' arranger.

The collaboration with Perry never brough chart success. However, in

artistic terms, Perry helped them reach a place no reggae band had reached

before, and very quickly. The bud was there - it would just take a little

longer before it flowered.

While Perry was working his distinctive brand of magic, King Tubby was

taking the young reggae in another direction. The DJ (a man who ‘toasted'

or rapped over instrumental tracks) had long been a staple of the sound

systems, and Tubby had one of the best in Ewart Beckford, known as

U-Roy.

Tubby had discovered that acetates, known as dub plates, could be

manipulated. The vocal track could be left off, creating a new ‘version'

of the song, something for U-Roy to toast over. When he put the two

elements together in a studio, he came up with something new. "Wake The

Town," record at Duke Reid's, was the first toasting record (although

producer Keith hudson claimed to have recorded U-Roy a year

earlier, on a version of Ken Boothe's hit "Old Fashion Way," retitled

"Dynamic Fashion Way"). It went directly to the top of the charts,

ushering in a new style that would be one of the parents of hip-hop.

Others followed the path. Big Youth, who began as a U-Roy

imitator before finding his own style, broke through with "S.90 Skank"

(named for a moped), and I-Roy (Roy Reid) followed with "Musical

Pleasure." But it was U-Roy who led the pack for the first half of the

1970s. He was one of the most political toasters of the time, putting out

records like "Sufferer's Psalm" (1974), which used the 23rd Psalm as a

springboard to condemn capitalism. It sold 27,000 in the Caribbean; not

earth-shattering but respectable for such an overtly political disc.

In the U.K. Trojan focused on the very commercial end of reggae,

"music," noted writer Sebastian Clarke, "with a beat, a soft melody and

strings behind it." It proved to be a potent combination. From 1970-75,

Trojan registered 23 top 30 hits from the likes of John Holt,

Bob and Marcia, Ken Boothe, Desmond Dekker, and Dave and Ansell

Collins. There were also two subsidiary labels, Attack and Upsetter,

for the work of producers Bunny Lee and Lee Perry. It was an affirmation

that the music could reach out beyond the Afro-Caribbean community, and

the success helped lay the groundwork for a revitalized. Bob Marley and

the Wailers, whose records would appear on Chris Blackwell's label,

Island.

From concentrating on Jamaican music, Blackwell had ventured into white

progressive rock in 1967, and quickly become one of the U.K.'s premier

labels in the field. But he'd retained his love of Jamaican music, and

held on to one artist he'd singed in 1965 - Jimmy Cliff.

He'd moved Cliff to England and carefully groomed him to become an

international artist, getting rid of the patois speech. And Cliff did

establish a strong following in France and Scandinavia. By 1967 he'd had a

British hit, "Give And Take," and released Hard Road to Travel,

which showed him as a soul balladeer. With the end of the decade he was

established as a hitmaker ("Wonderful World, Beautiful People," "Many

Rivers To Cross," and his cover of Cat Stevens's "Wild World" all

charted) and a songwriter, penning for Desmond Dekker ("You Can Get It If

you Really Want"), the Pioneers ("Let You Yeah Be Yeah"), and even

venturing into the political arena with "Vietnam," which Bob Dylan

described as "the best protest song ever written."

Cliff decided to return to Jamaica, and change his image by making

Another Cycle in Muscle Shoals, one of the homes of soul music, in

1971. However, the world wasn't ready for a reggae star going soul (that

would have to wait for Toots in Memphis a few years later), and the

record stiffed. Instead he turned to acting, starring in writer/director

Perry Henzell's film The Harder They Come.

The movie arrived in theaters in 1972, and Island released the

soundtrack album, which featured Cliff singing the title song, which was

also the lead single. Rumors circulated that the 45 never became a hit

because Island ignored store requests for more stock to prevent its

success, in an attempt to make the reluctant Cliff sign a further one-year

option with the label; they were offering 14,000GBP, and he was asking

20,000 (in 1973 Cliff wouls sign with EMI in the U.K., and Warner Bros. In

the U.S.).

More than anything before it, The Harder They Came brought

reggae and Jamaica to global attention, without any concessions to the

mass market. The characters all spoke in patois, virtually

incomprehensible to non-native ears, telling the story of a rude boy's

rise and fall in Kingston. The ghettoes were truthfully portrayed. The

soundtrack steered clear of the pop-reggae sound. While half of the

album's twelve tracks were from Cliff, the others were a selection of

reggae classics - "Rivers Of Babylon" (Melodians), "007 (Shanty

Town)" (Desmond Dekker), "Pressure Drop" (Toots and the Maytals), and of

the greatest rude boy anthems, the Slickers' "Johnny Too Bad." It

was reggae at its unvarnished best, not sweetened in any attempt to win

over new fans.

Between chart success and the film, reggae how had recognition. What it

needed was one person to bring together the disparate elements -

songwriting, musicianship, and image - that could fully establish reggae

both commercially and critically. It seemed like a tall order, but the

person was already there.

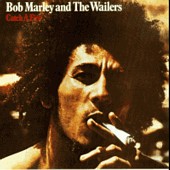

In 1972 the Wailers, with the Barrett brothers now part of the band,

moved to England to work for johnny Nash. Marley had preceded the others,

to work with Nash on the score of a Swedish film starring Nash (it was

never released). Once ensconced in a cheap London hotel, the Wailers

became the backup band for Nash's I Can See Clearly Now album, and

Marley signed a contract with CBS, who issued his "Reggae On Broadway."

Nash's promotion man, Brent Clarke, worked the single hard, but with no

record company support, it only sold 3000 copies. Soon Clarke was

expending all his energies on the Wailers, moving them into a house which

became a focal point for young black musicians.

When Nash left England for America, Clarke began work at Island, and

gave Blackwell a demo tape of songs Marley had written for Nash. Blackwell

was familiar with them, and had once considered signing them to Island,

before being dissuaded by their difficult reputation. Now Island were

looking for a reggae artist to replace Cliff, and the Wailers were in

danger of being deported. The timing was perfect for a deal.

For the meager sum of 8000GBP, and the right to release their own

records in the Caribbean, the Wailers became Island recording artists

(actually for the second time - Island had issued "Put It On" in 1965).

Borrowing money from Clarke, who'd brokered the deal, they returned to

Jamaica to record. At Dynamic Studios in Kingston, the tracks that made up

Catch A Fire were laid down, using not only the band, but also some

session men, including Robbie Shakespeare and Tyrone Downey.

When Marley (who at this stage did not have dreadlocks) delivered the

tapes to Blackwell in the winter of 1972, Blackwell could sense the

potential. With the right push, it could break reggae into the mainstream.

However, the sound was still too Jamaican, and so guitarist Wayne

Perkins and keyboard player Rabbit Bundrick were drafted in.

The finished album had both a rootsy feel and a fine rock sheen.

Island put a lot of marketing muscle behind Catch A Fire. It

came in a die-cut cover with guaranteed eye appeal. The disc, and the

band, received a great deal of press, and toured Europe and America; in

New York, they played a week at Max's Kanasa City, doing three 30-minute

sets a night. But a winter tour of the U.K. was abandoned, ostensibly

because of the cold.

The three core members of the Wailers had been together for a decade,

but with the flowering of real success, cracks in the unity began

appearing. Blackwell had formed a strong working relationship with Marley,

and was pushing him as the leader of the group, something neither Tosh nor

Wailer fully understood. But Tosh, who once pulled a machete on Blackwell,

was notoriously volatile and Wailer, still the only Rasta in the band,

refused to sign agreements and contracts, a nightmare for both label and

management.

Even with Island's might and money, Catch A Fire didn't make

international stars of the Wailers. The white rock world need more time to

absorb the new phenomenon (acceptance really came with Eric

Clapton's cover of Marley's "I Shot The Sheriff"). But it was the

record that became the foundation for reggae to become a global

phenomenon.

Roy Shirley says he made "Hold Them" in 1965. He could have done it

as a slow rhythm, but I don't think it was rock steady. Hopeton

Lewis went in to do a ska tune, "Take It Easy," and he couldn't manage

it on the rhythm, so he said to play it slow. They played it half-speed,

and when it was done, someone said to him, ‘That rock steady, man, that's

rockin' steady.' And that's how the name came about. He claims he was

before Studio One, Beverley's, everyone with rock steady (the record was

released on Federal)."

Roy Shirley says he made "Hold Them" in 1965. He could have done it

as a slow rhythm, but I don't think it was rock steady. Hopeton

Lewis went in to do a ska tune, "Take It Easy," and he couldn't manage

it on the rhythm, so he said to play it slow. They played it half-speed,

and when it was done, someone said to him, ‘That rock steady, man, that's

rockin' steady.' And that's how the name came about. He claims he was

before Studio One, Beverley's, everyone with rock steady (the record was

released on Federal)."